HONG KONG — Chinese President Xi Jinping is turning on the charm as he looks to sweep up the shards of America’s shattered economic relationships.

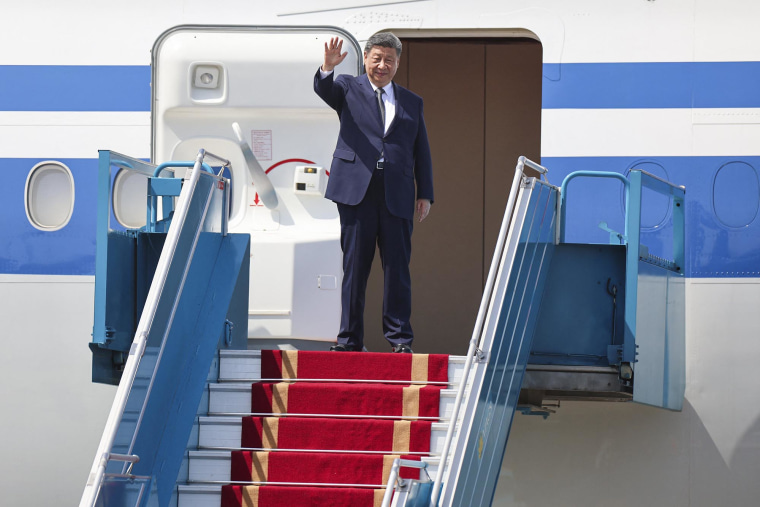

As the world’s markets and leaders try to absorb the impact of the market chaos unleashed by the Trump administration’s announcement and softening of sweeping tariffs on almost all U.S. trading partners, Xi embarked on a trip through Southeast Asia. After a visit to Vietnam, he landed in Malaysia on Tuesday.

“A trade war and tariff war will produce no winner, and protectionism will lead nowhere,” he wrote in the Vietnamese newspaper Nhan Dan. “Our two countries should resolutely safeguard the multilateral trading system, stable global industrial and supply chains, and an open and cooperative international environment.”

President Donald Trump has interpreted Xi’s words, as well as his Chinese counterpart’s meetings with the leaders of the major economies in China’s backyard, as Beijing getting together for a “lovely meeting” with one of the countries worst hit by tariffs “to figure out, ‘how do we screw the United States of America?’”

The message Xi is sending on his tour is loud and clear. China is seeking to capitalize on the Trump administration’s truculence to cast itself as the world’s preferred trading partner.

That Xi’s rare Southeast Asian tour started with Vietnam is no accident. Trump’s punishing 46% tariff on the country will hammer the economy of a country that is the sixth largest source of U.S. imports and a third of whose gross domestic product relies on trade with the U.S.

After Malaysia, which received a 24% levy from the U.S., Xi is expected to visit Cambodia — hit by 49% duties. He will do so after telling his Vietnamese counterpart, To Lam, that Beijing and Hanoi must “jointly oppose unilateral bullying and safeguard the global free trade system,” according to China’s state-run broadcaster CCTV News.

Xi’s junket is just the beginning of a broader response to Trumponomics, analysts say.

The Chinese leader “happily sees Donald Trump destroying, undermining, discrediting, deliberate international order in order to make it easier for him to push for the transformation of the international order into something ‘better,’” says Steve Tsang, director of the China Institute at the SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies) University of London.

Winning over Southeast Asia, with its developing economies already largely dependent on Beijing, will be the easy part.

Slightly more difficult for Xi will be supplanting the U.S. as the biggest trading partner of the European Union.

Last week, Xi told Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez that the bloc should join forces with China to oppose “unilateral bullying” and defend the “international rules and order” — words almost identical to ones he used this week in Hanoi.

While Beijing followed that up Monday with a statement emphasizing Sino-European unity, Washington has made things easy for Xi, says Wang Dong, executive director of Peking University’s Institute for Global Cooperation.

“China doesn’t have to “drive a wedge” between the U.S. and its allies,” Wang told NBC News. “Rather, the bullying and cruel manner the Trump administration rolled out the punitive tariffs, along with the unpredictability and selfishness manifested by the U.S., have already driven US allies and partners closer to Beijing.”

A thaw in relations has already begun. E.U. leaders last week agreed to revive negotiations on the prices of electric vehicles — they imposed a 45% tariff on low-emission Chinese cars in October — despite fears that Chinese products may flood the European market if the U.S. keeps in place its 145% levy on Chinese imports.

But that softening comes amid a raft of economic disputes between the world’s second- and third-largest economies. It may also be difficult to achieve more due to China’s one-party rule and concerns over human rights allegations.

“Lots of people don’t share China’s political values,” said Kerry Brown, professor of Chinese studies and director of the Lau China Institute at King’s College London.

More difficult still will be warming up long-standing U.S. allies in Asia — specifically Japan and South Korea — whose economies will suffer the effects of 24% and 25% tariffs respectively, despite them scrambling teams of trade envoys within days of the tariff announcements.

The U.S. is both countries’ main guarantor against security threats from China and Russia, and Tokyo’s and Seoul’s reactions are best summed up by the South Korean Foreign Ministry’s comment Monday that “bilateral dialogue with the United States is the most effective way to resolve the issue of U.S. tariff measures.”

But with China both countries’ largest trading partner and Washington’s increasingly spotty loyalty mean South Korea and Japan are essentially “caught in a quandary,” Brown said. “China is still practically a power you have to deal with.”

And if the carrot doesn’t work, there’s always the stick. Beijing holds at least one key piece of leverage over Washington and its allies.

China held more than $700 billion in U.S. government bonds — the proceeds from which the U.S. Treasury finances public expenditure — making it among the largest holders of such bonds.

If China sells those bonds, it will threaten America’s ability to finance its debt, Brown said.

Between that, and Beijing wearing the reassuring face of a reliable trading partner, “China’s got itself into a relatively good position,” he added. “And it annoys the hell out of America.”