BBC News

Getty Images

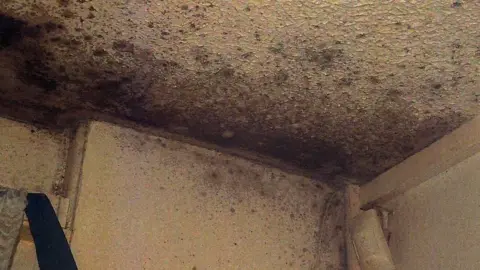

Getty ImagesComplaints about substandard living conditions in social housing in England are more than five times higher than five years ago, according to the housing watchdog.

Housing Ombudsman Richard Blakeway told the BBC an “imbalance of power” in the tenant-landlord relationship was leading to “simmering anger” among those living in social housing.

He warned without change England risked the “managed decline” of social housing.

Asbestos, electrical and fire safety issues, pest control and leaks, damp and mould are among the complaints, the watchdog receives .

In its latest report, the Housing Ombudsman, which deals with disputes between residents and social housing landlords in England, said that the general condition of social housing – combined with the length of time it takes for repairs to be done – is leading to a breakdown in trust.

“You’ve got ageing homes and social housing, you’ve got rising costs around materials, for example, and you’ve got skills shortages,” said Mr Blakeway, who spoke to the BBC Radio 4’s Today programme.

“You put all that together and you end up with a perfect storm and that’s what’s presenting in our case work. That is not sustainable.”

He said tenants have “little say in the services they receive, however poor they are” and that this is leading to “growing frustration”.

While he acknowledged that social landlords are putting in “record amounts” for repairs and maintenance – £9bn between 2023 and 2024 – there had been historic underfunding in social housing.

He also said that while landlords have faced “funding uncertainties”, they needed to address their communication with tenants that sometimes “lacks dignity and respect”.

According to the ombudsman’s report, there were 6,380 complaints investigated in the year to March 2025 – up from 1,111 in the year to March 2020.

It also found that an estimated 1.5 million children in England live in a non-decent home in 2023, and 19% of those live in social housing.

It is calling for a “transformative overhaul” of the current system, including an independent review of funding practices and the establishment of a “national tenant body” to “strengthen tenant voice and landlord accountability”.

That would be separate to the ombudsman, which has the power to order a landlord to apologise, carry out works or pay financial compensation.

“The human cost of poor living conditions is evident, with long-term impacts on community cohesion, educational attainment, public health, and economic productivity,” said Mr Blakeway.

“Without change we effectively risk the managed decline of one of the largest provisions of social housing in Europe, especially in areas of lowest affordability.

“It also risks the simmering anger at poor housing conditions becoming social disquiet.”

Rochdale Coroner’s Office

Rochdale Coroner’s OfficeHousing campaigner Kwajo Tweneboa told the BBC that he was “shocked but not surprised” by the ombudsman’s report.

He pointed out that for complaints to reach the ombudsman, tenants will have to formally raised the issue with the landlord.

Mr Tweneboa said social housing residents he has spoken to say they feel they are not listened to and that the culture within housing organisations “just isn’t right”.

“They feel they are just a rental figure at the end of each month.”

“In some cases, residents are left to suffer for years,” Mr Tweneboa says, adding that he knows of instances in which families with children have to “defecate in bin bags, urinate in bottles because they’ve been without a toilet for months”.

In a statement, a Ministry of Housing spokesperson said: “Everyone deserves to live in a safe, secure home and despite the situation we have inherited, we are taking decisive action to make this a reality.”

“We will clamp down on damp, mould and other hazards in social homes by bringing in Awaab’s Law for the social rented sector from October, while we will also introduce a competence and conduct standard for the social rented sector to ensure staff have the right skills, knowledge and experience to do their jobs effectively.”