Business reporter

Maddy Savage

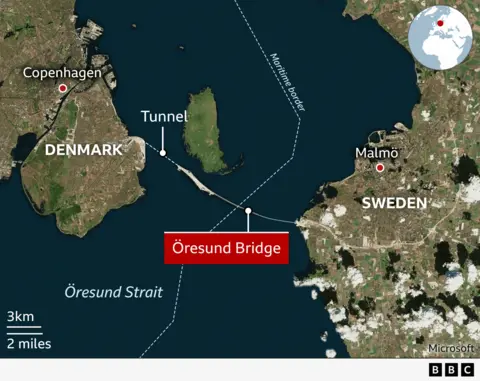

Maddy SavageOne of Europe’s most iconic transport landmarks, the Öresund bridge, which connects Denmark and Sweden, is celebrating 25 years since its opening. But challenges remain despite its huge impact on business in the region.

Oskar Damkjaer, 28, is standing on a platform inside the red-brick 19th century train station in Malmö.

He lives in the Danish capital, Copenhagen, and commutes over the Öresund bridge to Sweden’s third largest city twice a week, folding some of his working hours into the high-speed 40-minute train journey.

“People think that it’s a really big thing to commute to another country,” says the software engineer who works for Neo4j, a Swedish-founded database company. “It’s quite convenient, I would say.”

Across the bridge in Copenhagen, Laurine Deschamps is sitting at her desk at Danish gaming company IO Interactive’s sleek, minimalist office.

She previously worked for a Swedish-owned game studio in Malmö, and decided to keep living there when she scored a job at IO Interactive’s headquarters in Copenhagen, which she commutes to four times a week.

“Some people would pick [to live in] Copenhagen, to be in a bustling, capital city with lots of activities,” says the global brand manager.

“I very much prefer Malmö – it’s a human-sized city, you can walk everywhere.”

Maddy Savage

Maddy SavageTheir stories are the epitome of what Sweden and Denmark’s governments envisioned when they signed an agreement in 1991 to build a permanent link across the Oresund strait.

The goal was to maker travel faster and easier (commuters previously relied on ferries or short-haul flights), improve regional integration and boost economic growth.

It cost 30bn Danish krone ($4.3bn; £3bn) and was built in five years.

A quarter of a century since its construction, the link remains the longest road and rail bridge in the EU, measuring 16km, including a tunnel section.

The journey across offers commuters cinematic views across the water, and its giant metal pylons are striking. The infrastructure inspired one of Scandinavia’s most successful TV franchises, cross-border crime drama The Bridge, which was a global hit in the 2010s.

Figures released in May by Öresundsinstitutet, an independent research organisation in the region, highlight the broader impact the bridge has had on transport and business trends as it marks its 25-year jubilee.

Cross-border commuting has increased by more than 400% (although exact comparisons are tricky due to shifting data collection methods).

The number of Swedes and Danes moving to the other side of the bridge has risen by more than 60%.

Plus, the link has helped thousands of people start businesses on the opposite side of the water.

There has been a 73% increase in these sorts of companies, according to Öresundsinstitutet’s data.

“We have this very unique opportunity of being able to go back and forth,” says Sandra Mondahl, a senior manager at IO Interactive, who helped launch the firm’s sister studio in Malmö in 2019.

“It makes me very empowered to be able to contribute to the development of both game development scenes — in Denmark and in Sweden,” says the 33-year-old, who is originally from Copenhagen.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesÖresundsinstitutet’s research also suggests more than 100 businesses have relocated their Swedish headquarters or specialist offices to Malmö since the bridge opened, creating thousands of new job opportunities in the former industrial city.

These include parts of the Ikea Group and Ikano, a Swedish bank.

“Many big Danish companies have placed their Swedish offices in Malmö instead of Stockholm [the Swedish capital] too — big pharma companies for example,” says Öresundsinstitutets CEO Johan Wessman.

The institute’s research suggests that alongside improved access to a larger skilled labour pool on both sides of the Öresund strait, Malmö is attractive for business owners due the availability of modern office space in newly developed areas close to its stations, and its proximity to Copenhagen international airport.

Increased access to talent due to the Öresund bridge link has also played a major role in driving innovation in the region.

Malmö has experienced a surge in new tech start-ups and life science companies. Lund University research published in 2022 found there has been a steeper increase in the number of patents in relation to its population size compared to Sweden’s other major regions, Gothenburg and Stockholm.

A separate 2022 study by the university’s economics department suggested Danish-Swedish trade in the region is 25% higher than it would have been if the bridge had never been built.

Öresundinstitutets research indicates that record numbers of people commuted by train in 2024 – making almost 41,000 journeys per day.

This reversed a dip during the pandemic, when border controls and reduced services caused major disruptions.

However, Mr Wessman says that the increasing popularity of cross-border commuting means overcrowding is now becoming an issue, with larger “future generation trains” designed to relieve the pressure not due to be rolled out until at least 2030.

Despite the boom in company relocations to Malmö, and the region’s reputation for innovation, Öresundsinstitutet’s data also suggests that the Swedish city still has work to do to encourage commuting from Denmark. More than 95% of commuters travel in the opposite direction, from Malmö to Copenhagen.

“Malmö is a regional city. In a capital, you have the kind of jobs that don’t exist in a smaller city, [and] you have higher salaries in Copenhagen than in Malmö,” explains Mr Wessman.

Anja Ekstrom

Anja EkstromBoozt, a Danish-owned online fashion marketplace which established its headquarters in Malmö in 2010, recently announced it was moving its head office to Copenhagen.

Its CEO and co-founder Hermann Haraldsson says that while he has personally enjoyed commuting to Malmö for the past 15 years, it has become increasingly tricky to lure young Danish talent away from the buzzing capital.

“I think there is a mental barrier for some Danes to cross the bridge and work in Sweden,” he says, acknowledging that many Copenhagen residents endure longer daily commutes within the city, compared to typical journey times over the bridge.

“Since we announced the move, I believe that the amount of applications for open positions has tripled.”

Mr Haraldsson also believes that commuting over the Öresund bridge is too expensive.

The price of a one-way train journey from central Copenhagen to Malmö is around $17 (£13; €15) and takes about 40 minutes. It costs about $80 to drive a car over, although there are big discounts for regular travellers.

The CEO argues that there are too many administrative hurdles for cross-border workers too, since Sweden and Denmark have different pension, parental leave and unemployment insurance systems.

A new agreement between the two countries came into force in January, designed to simplify income tax rules for commuters.

Cultural integration has also been trickier than Swedish and Danish authorities envisioned, says Öresundsinstitutet CEO Wessman.

He notes that while the Nordic nations may “look very similar” to global observers, differences in working cultures can mean that business people struggle to understand each other “despite good intentions”.

“Danes are known for being the most blunt out of the Scandinavian cultures…whereas Swedes are known as being a little bit more consensus-seeking,” adds Mondahl, the Copenhagen-born gaming manager now based in Malmö.

“When I first arrived in a Swedish work environment…there were a lot of meetings and everybody needed to be ‘heard’ for everything, and it’s about figuring out how to get the most out of that,” she says.

Despite these challenges, the bridge remains a global icon for both cross-border and regional collaboration.

It helped inspire the Fehmarnbelt, a new tunnel being built under the Baltic Sea between Denmark and Germany, designed to further improve Scandinavia’s links with the rest of Europe. Finland is also exploring a new bridge across the Baltic sea, connecting the city of Vaasa with Umeå in northern Sweden.

Mr Wessman argues that the importance of these types of secure fixed links is heightened against the backdrop of the war in Ukraine, and Sweden and Finland’s recent accession to Nato, which includes a commitment to assisting other member states.

Swedish and Danish authorities are also discussing several potential new cross border connections.

These include road and rail tunnels to Denmark from either the Swedish city of Helsingborg or Landskrona (both in the south west of Sweden), and a new subway connecting Malmö and Copenhagen.

“I think it will take several more years before the next connection is ready to be inaugurated. But it will come, and it will be needed,” says Mr Wessman.