South America correspondent

Science correspondent

NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory

NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin ObservatoryA powerful new telescope in Chile has released its first images, showing off its unprecedented ability to peer into the dark depths of the universe.

In one picture, vast colourful gas and dust clouds swirl in a star-forming region 9,000 light years from Earth.

The Vera C Rubin observatory, home to the world’s most powerful digital camera, promises to transform our understanding of the universe.

If a ninth planet exists in our solar system, scientists say this telescope would find it in its first year.

RubinObs

RubinObsIt should detect killer asteroids in striking distance of Earth and map the Milky Way. It will also answer crucial questions about dark matter, the mysterious substance that makes up most of our universe.

This once-in-a-generation moment for astronomy is the start of a continuous 10-year filming of the southern night sky.

“I personally have been working towards this point for about 25 years. For decades we wanted to build this phenomenal facility and to do this type of survey,” says Professor Catherine Heymans, Astronomer Royal for Scotland.

The UK is a key partner in the survey and will host data centres to process the extremely detailed snapshots as the telescope sweeps the skies capturing everything in its path.

Vera Rubin could increase the number of known objects in our solar system tenfold.

NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory

NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin ObservatoryBBC News visited the Vera Rubin observatory before the release of the images.

It sits on Cerro Pachón, a mountain in the Chilean Andes that hosts several observatories on private land dedicated to space research.

Very high, very dry, and very dark. It is a perfect location to watch the stars.

Maintaining this darkness is sacrosanct. The bus ride up and down the windy road at night must be done cautiously, because full-beam headlights must not be used.

The inside of the observatory is no different.

There is a whole engineering unit dedicated to making sure the dome surrounding the telescope, which opens to the night sky, is dark – turning off rogue LEDs or other stray lights that could interfere with the astronomical light they are capturing from the night sky.

The starlight is “enough” to navigate, commissioning scientist Elana Urbach explains.

One of the observatory’s big goals, she adds, is to “understand the history of the Universe” which means being able to see faint galaxies or supernova explosions that happened “billions of years ago”.

“So, we really need very sharp images,” Elana says.

Each detail of the observatory’s design exhibits similar precision.

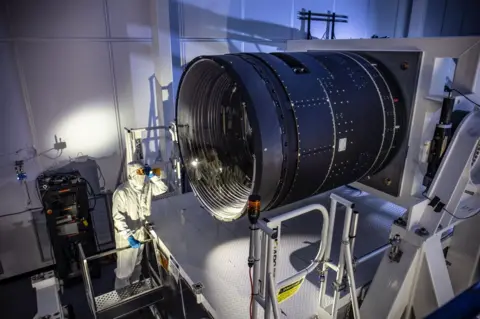

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

SLAC National Accelerator LaboratoryIt achieves this through its unique three-mirror design. Light enters the telescope from the night sky, hits the primary mirror (8.4m diameter), is reflected onto the secondary mirror (3.4m) back onto a third mirror (4.8m) before entering its camera.

The mirrors must be kept in impeccable condition. Even a speck of dust could alter the image quality.

The high reflectivity and speed of this allow the telescope to capture a lot of light which Guillem Megias, an active optics expert at the observatory, says is “really important” to observe things from “really far away which, in astronomy, means they come from earlier times”.

The camera inside the telescope will repeatedly capture the night sky for ten years, every three days, for a Legacy Survey of Space and Time.

At 1.65m x 3m, it weighs 2,800kg and provides a wide field of view.

It will capture an image roughly every 40 seconds, for about 8-12 hours a night thanks to rapid repositioning of the moving dome and telescope mount.

It has 3,200 megapixels (67 times more than an iPhone 16 Pro camera), making it so high-resolution that it could capture a golf ball on the Moon and would require 400 Ultra HD TV screens to show a single image.

“When we got the first photo up here, it was a special moment,” Mr Megias said.

“When I first started working with this project, I met someone who had been working on it since 1996. I was born in 1997. It makes you realise this is an endeavour of a generation of astronomers.”

It will be down to hundreds of scientists around the world to analyse the stream of data alerts, which will peak at around 10 million a night.

The survey will work on four areas: mapping changes in the skies or transient objects, the formation of the Milky Way, mapping the Solar System, and understanding dark matter or how the universe formed.

But its biggest power lies in its constancy. It will survey the same areas over and over again, and every time it detects a change, it will alert scientists.

RubinObs

RubinObs“This transient side is the really new unique thing… That has the potential to show us something that we hadn’t even thought about before,” explains Prof Heymens.

But it could also help protect us by detecting dangerous objects that suddenly stray near Earth, including asteroids like YR4 that scientists briefly worried early this year was on track to smash into our planet.

The camera’s very large mirrors will help scientists detect the faintest of light and distortions emitted from these objects and track them as they speed through space.

“It’s transformative. It’s going be the largest data set we’ve ever had to look at our galaxy with. It will fuel what we do for many, many years,” says Professor Alis Deason at Durham university.

She will receive the images to analyse how far back the stars reach in the Milky Way.

At the moment most data from the stars goes back about 163,000 light years, but Vera Rubin could see back to 1.2 million light-years.

Prof Deason also expects to see into the Milky Way’s stellar halo, or its graveyard of stars destroyed over time, as well as small satellite galaxies that are still surviving but are incredibly faint and hard to find.

Tantalisingly, Vera Rubin is thought to be powerful enough to finally solve a long-standing mystery about the existence of our solar system’s Planet Nine.

That object could be as far away as 700 times the distance between the Earth and the Sun, far beyond the reach of other ground telescopes.

“It’s gonna take us a long time to really understand how this new beautiful observatory works. But I am so ready for it,” says Professor Heymans.

Get our flagship newsletter with all the headlines you need to start the day. Sign up here.