Buried in a 12-page analysis prepared for the government by the Council for Science and Technology (CST) is recognition that Labour’s action plan for artificial intelligence (AI) opportunities lacks any concrete support for semiconductors.

In June, Labour unveiled its industrial strategy, which includes £19m of funding to establish a UK semiconductor centre that will serve as a single point of contact for global firms and governments to engage with the UK semiconductor sector. The Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) said the centre would help ambitious firms scale up, form new partnerships and strengthen the UK’s role in global supply chains – helping to grow the economy.

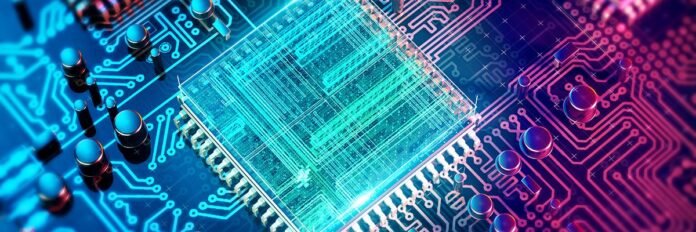

But while the UK starts to build a viable semiconductor sector, the world is moving ahead at an incredible pace due to the growth of AI and the need for AI acceleration chips. The CST believes the UK needs to develop a workforce of chip designers, especially in the area of optoelectronics, which it predicts will be essential to provide the high-speed interconnects required to enable the connectivity of large numbers of graphics processing units (GPUs) to support advances in AI inference and training.

AI chips are forecast to be the largest growth area in the chip industry for the next decade. The authors of the Council for Science and Technology’s Advice on building a sovereign AI chip design industry in the UK analysis noted that there are disproportionate opportunities for businesses – and nations – with the right capabilities, given that six of the seven largest companies in the world are investing billions where they perceive low-hanging fruit for more efficient, faster, lower power AI chips.

The government has a 50-point plan of action for AI, which includes establishing AI growth zones. The CST’s analysis states that “the plan is quiet on UK-designed chips for AI despite the opportunity and the risks”

While there are disproportionate opportunities, the UK should look at the possibility of having a stake in AI chips, which the Council for Science and Technology said would “also help us secure our hardware supply chain for domestic commercial and military applications, in an uncertain era of tariffs and export restrictions”.

This is now more relevant than ever, given recent policy changes in the US, and the risk that US semiconductor technology may be a key bargaining chip that US trade negotiators put into play to exert pressure on trading partners.

Earlier in August, Associated Press reported that Nvidia and AMD had agreed to share 15% of their revenues from chip sales to China with the US government, as part of a deal to secure export licences for the semiconductors.

Some industry watchers have remarked that this sets a dangerous precedent. Policy institute Chatham House warned that while the US administration has argued the case for restricting export of high-end semiconductors to China on grounds of national security, the levy being imposed by the Trump administration represents a way to exert pressure on certain countries.

“The deal sets a concerning precedent with long-term ramifications. It suggests that other companies active in strategic industries could potentially in future pay their way out of burdensome and complex export control regimes, even if they involve key US national security concerns,” wrote Katja Bego, a senior research fellow in Chatham House’s International Security programme, in a recent post on the Chatham House website.

She warned that this kind of arrangement could also set the scene for the Trump administration to more broadly exercise its ability to control export licensing to influence companies whose supply chains involve the US, such as the high-tech sector.

Compound semiconductors

The UK government’s semiconductor strategy sees a big role for compound semiconductors. However, the Council for Science and Technology believes optoelectronics – a compound chip heavily used in AI acceleration for ultra-fast connectivity of GPUs – should be prioritised. Its analysis points out that targeted investment could require trade-offs.

“Although the UK has a history of investing in compound materials, DSIT should consider deprioritising them in favour of activity in support of AI chips. Within the field of compound materials, optoelectronics should continue to be a relatively high priority as the market for it is expected to grow at a greater rate,” said the CST.

According to the Council for Science and Technology, data communications inside a single cloud datacentre are about 10,000 times larger than the entire public internet. “A single rack of AI accelerators communicates about 10 times faster than an equivalent rack of CPUs [central processing units]. Hence, AI systems already require more communications and are growing faster still,” said the report.

The report’s authors said this is good news for the UK, due to the nation’s strength in all aspects of optoelectronics, from optical subsystems and modules to specialised manufacturing. “We can anticipate far larger growth in manufacturing processes for optoelectronics than other compound manufacturing,” they wrote.

The Council for Science and Technology also recommended that the government explore investment in advanced chip assembly and packaging.